1 Knjige - 16,00 €

View basket “Searching for Ivana” has been added to your basket.

Some Call them Lady-Writers

14,60 €This study in literary history brings to light various characteristics of the Croatian female literary scene in the late 19th and early 20th century. Focusing on three key figures – Dragojla Jarnević, Jagoda Truhelka and Ivana Brlić Mažuranić – the author makes visible a complex tissue of influences, shared existential preoccupations, positions on writing and recurrent literary motifs. The fundamental question leading her research – what was it like to be a female writer in a period where writing was still largely attributed to a male intellect? – thus gets a rich answer that tries to restore justice to silenced female voices. As the area of Croatian female literature is still largely unexplored, Dujić’s study presents an almost pioneering work that brings the reader not only a historical analysis, but also excerpts from previously unpublished archive materials: letters, diaries and personal notes by the three great writers around whom this book revolves.

The Marriage Diaries

14,60 €The edition that will thrill every classical music lover! The year is 1840, in the city of Leipzig; the young but already internationally famous pianist Clara Wieck and the still quite unknown composer Robert Schumann just succeeded in getting married, despite various obstacles. The day after the wedding, upon Robert’s whish, they start writing down all their needs and desires, joys and sorrows of matrimonial life. They take turns in writing, each of them covering the events of one week, at first with a lot of passion. Many celebrated musicians of the period pass through the pages of their double diary; Robert and Clara speak about art, home concerts, days and weeks filled with music, but they also speak about love. In these first years of their marriage, years that have been among the most productive for Robert and a sort of setback for Clara, life is good, but it isn’t without its’ own shadows…

Self-Portrait in the Study

14,60 €Self-Portrait in the Study, the recently published autobiography of one of the leading contemporary continental philosophers Giorgio Agamben offers the reader a wide set of interesting motives. Throughout the book, the author recalls all the intellectual encounters which had a decisive influence on his thought, creating, in this way, a magnificent portrait of the late 20th century philosophical and literary scene: following Agamben from encounter to encounter, the reader meets Martin Heidegger, Guy Debord, Giorgio Manganelli, Elsa Morante, Ingeborg Bachmann, Gershom Scholem… The descriptions of these meetings and friendships are interlaced with authentic philosophical meditations on painting, language, poetry, history and inheritance, and, in the final analysis, with glimpses of that “universal science of man” about which Agamben dreamt together with Italo Calvino and Claudio Rugafiori. Agamben’s autobiography thus offers a lyrical synthesis of the three elements whose endless perturbations characterize the whole of the philosopher’s oeuvre: literature, philosophical discourse and a private life that must remain hidden forever.

Book #2912

Joseph Conrad as I Knew Him

9,29 €In these biographic fragments Jessie Conrad sketches the picture of her husband Joseph, one of the greatest writers of English twentieth century literature: nervous, a bit weird, attached to his family in his own way, but first of all, obsessed with his work. At the same time, the reader catches a glimpse of Jessie herself, the almost ideal writer’s wife of old times: typing his texts, cooking, economizing, welcoming guests, raising the children, coping with reality in every possible way instead of Joseph. But the act of writing puts her beyond the role of mother, wife and housewife: taking the courage to write down this intimate testimony, she creates a place for herself in Conrad’s verbal space and becomes a writer in her own right.

Berlin Childhood around 1900

7,96 €Over the last few decades Walter Benjamin has become one of the most prominent names in the humanities: considering definitions of modernity, film theory, philosophy of history, cultural studies or criticism of canonical literary texts, his work can hardly be avoided. This is brought about by Benjamin’s broad interests and lucidity, but also by his awareness of the fact that cultural theory or philosophy always implies an act of writing. His penchant towards the use of metaphor, image, allusion rather than systematical argumentation and his insistence on a purified stile rather than a strict composition make Benjamin’s texts – that always place themselves between philosophy and literature – a field of knowledge that never allows an unambiguous interpretation. In his Berlin Childhood around 1900 the dominant element is precisely this ‘surplus’ of literature; applying an autobiographical discourse, Benjamin creates a lyrical picture of his childhood in a rich bourgeois family from Berlin. Nevertheless, this seemingly personal thematic becomes a historically relevant document that bears witness to the life and culture of the big city, evoking a great number of social and philosophical issues: the constitution of subject through memory, the shadow of class struggle, the possibility of objective historical representation, the relation between modernism and messianism. Starting from a specific literary genre, Berlin Childhood around 1900 amplifies the tension between philosophy and literature, the tension that makes them both possible: thus Benjamin anticipates some of the most important themes and techniques of post-structuralism, and stays as modern as ever.

Letters to his Wife 1914-1917

9,29 €My dearr heart, my lovely little one – thus begin the gentle letters Henri Barbusse wrote to his wife a hundred years ago. What follows is by no means gentle – trenches, shells, mud and the dead, the war that is revealed in its bloody meaninglessness. In the year 1914. the writer of letters, Henri Barbusse, was 41, had a reputation as a writer and editor, was not in the best health and had firm pacifist beliefs. Despite all this he volunteered for the French Army and spent the two first years of war on the front lines – and wrote his novel Under Fire, literary testimony of the World War I, which earned him the Goncourt prize and thousands of readers. Documentary material on which is based his novel is found in the letters he wrote almost daily to his wife Hélyonne. In their immediacy and authenticity, those letters can convey to the reader of today the drama of the beginning of the “short twentieth century” better than any fiction.

Logbook

7,96 €Logbook by Austrian writer Franz Hammerbacher was written during the voyage around the world on large container ships, the voyage which, accidentally, lasted eighty days. Discrete humor, actuality and elegant style brought the author a number of readers and critical acclaim.

Ship’s log is a means of the preservation of evidence, but it remains unclear what it was to be proved by it. The meaning of the notes is created only retroactively. It is vital that the log is kept chronologically and politely, regardless of the current mood and inspiration. Extraordinary events are recorded as rarely as they occur. Ship’s diary in the first place is the record of everyday life . Using the logbook method, Franz Hammerbacher reports on events such as the spectacular passage through the Panama Canal or the dangerous waterways near the Somali coast, as well as on the small events in the lives of crews and passengers, drawing the reader into his documentary story that slides almost imperceptibly from the recorded moments on the sea into the meditation about the voyage that is life.

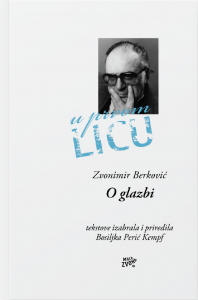

On Music

7,96 €A collectionof music critiques and essays by Croatian film director and erudite Zvonimir Berković. Texts he wrote over several decades for newspapers and magazines are collected in this book and divided into four parts: Critique – Portraits – Meditations – Conversations. Collected and edited by Bosiljka Perić Kempf.

Zvonimir Berković wrote about music only occasionally, in the mid sixties and the first half of the seventies, for several newspapers and magazines. He left chronicles of the music lives of festival cities as Dubrovnik and Vienna, but he also wrote reviews of both local and foreign artists’ performances during the Zagreb concert season. Most interesting, however, are the author’s imagination and subtle (and not only musical) taste in the portraits of musicians, interpreters and composers. Music had a deep impact in Berković’s work of movie director, especially in his “Rondo”, a Croatian classic made in 1966.

Searching for Ivana

16,00 €A biographical novel by Sanja Lovrenčić about the Croatian author Ivana Brlić Mažuranić. Written in the first-person singular, the story develops on two levels, in the past and in the present, unfolding around the changing and yet unchanging topics of family relations, artistic creation and female existence in the world of literature.

“K.Š.Gjalski” Award for the best Croatian novel in 2007.

Scorpion-Fish

7,96 €A literery testimony of an outward and inward journey by the renowned Swiss traveler and writer. What could have eassily become a simple travelogue becomes a diary of a slow sinking into loneliness, fever, exotic beauties and deadly menaces of a “chimerical island” – Sri Lanka. Combining humour and poetry, N. Bouvier created penetrating, unforgettable literary images.

Feminine Side of the Croatian Literature

7,96 €Exploring the feminine side of Croatian literature Lidija Dujić offers a concise and interesting overview of selected segment of the Croatian literary history. She gives biographial sketches of Croatian female writers, explores the reception of their work and cliche images of women writers from the times of Renaissance to the contemporary age. Analyzing and re-valuing some works, recognized under the label of “women’s literature”, the author challenges many commonplace notions – writing in first person singular. The book is based on her doctoral dissertation, but is intended for a wider audience.

Good Morning, World!

7,96 €Diaries by the famous Croatian writer Ivana Brlić Mažuranić, written in the 1880s when she was fifteen to eighteen years old. The book provides insight into teenage life in the 19th century in Zagreb, the charming young character of the writer, her thoughts on literature, life and death, as well as the seeds of conflicts awaiting a female writer – all of which makes it a highly interesting read.

Letters from Sweden, Norway and Denmark

10,00 €Famous letters by Mary Wollstonecraft for the first time in Croatian translation.

Searching for Ivana

Searching for Ivana